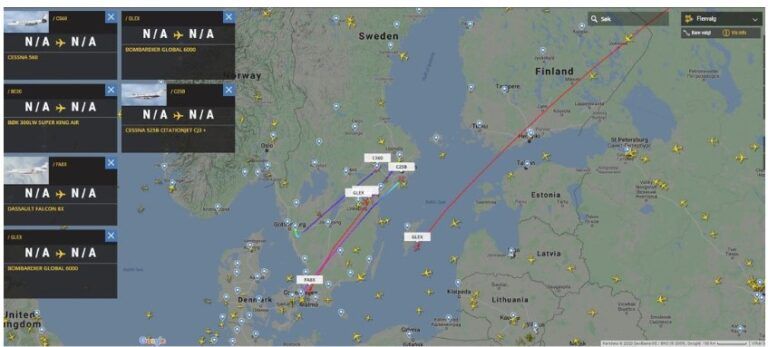

| Siden minst 1958 har militæret engasjert seg i å sprøyte partikler i luften antagelig for å studere værendring. Disse aktivitetene var sporadiske i tid og sted. Men rundt 2010, under Obama-administrasjonen, ble sprøyting av partikler fra luften en nesten daglig aktivitet over hele Nord-Amerika, EU, Det britiske samveldet og andre land, inkludert Kina, Egypt, India, Russland og kanskje andre. Dette var en skjult aktivitet med fornektelse og desinformasjon tilsynelatende koordinert på alle myndighetsnivåer. Ingen informasjon ble gjort tilgjengelig om partikelsammensetningene sprøytet i luften vi alle puster inn, og ingen informasjon om potensielt skadelige helserisiko. Følgende er utsagn / spørsmål med lenker til svar:J. Marvin Herndon, PhD og Mark Whiteside, MD, MPH til dags dato er de eneste forskerne som publiserer i den fagfellevurderte vitenskapelige litteraturen om sammensetningene og folkehelserisikoen ved sprøyting fra luften:● Vitenskapelige og medisinske humanitære publikasjoner (klikk her)● Bevis for ukjent global geoteknikk (klikk her)Samlet innsats for å lure det medisinske samfunnet og innbyggerne i folkehelserisikoen ved sprøyting ved å lyve, tvinge og presse redaktører og journalpersonell til å trekke fagfellevurderte og publiserte folkehelsevitenskapelige artikler (klikk her).Hvordan kan en ikke-forsker forstå sprøyting fra luften og dens konsekvenser, spesielt for helsen? En måte er å lytte til og se på de vitenskapelig korrekte musikkvideoene hvis tekster ble skrevet av J. Marvin Herndon. (Klikk her)Hva sprøyter de ut i luften vi puster inn? Rettsmedisinske vitenskapelige undersøkelser stemmer overens med kullflyveaske, det giftige avfallsproduktet fra kull som er det viktigste stoffet som sprøytes ut i luften vi puster inn (klikk her).Hvordan påvirker partikler som sprøytes i luften været? Vedvarende sprøyting av partikler i områdene der det dannes skyer (1) hemmer nedbør til det kraftige regnskyllet, den såkalte “tørke eller flod” -effekten, (2) varmer opp atmosfæren, (3) forsinker varmetapet fra Jorden, og (4) absorberer sollys når den faller til jorden. Kort sagt, sprøyting fra luft ødelegger den naturlige værsyklusen, forurenser jordens biosfære og forårsaker global oppvarming – konsekvenser som feilaktig blir skyldt på forbrenning av fossilt brensel.Tørking i California: Sett scenen for branner i California (klikk her).Hvordan kan sprøyting fra luften skade menneskers helse? De skadelige folkehelseeffektene av aerosolisert partikler kan utledes fra forurensningsstudier av partikler 2,5 mm og mindre. Eksponering for slike partikler har vist seg å være assosiert med økt sykehusinnleggelse, sykelighet og for tidlig dødelighet, risiko for hjerte- og karsykdommer og lungekreft, andre lungesykdommer inkludert astma, diabetes, risiko for hjerneslag, Alzheimers sykdom, redusert nyrefunksjon hos eldre menn, lav fødselsvekt, redusert mannlig fruktbarhet og nedsatt kognitiv evne hos eldre kvinner. Uønskede helseeffekter av aerosolisert kullflyveaske (CFA) inkluderer (1) nevrologiske lidelser, slik som autismespektrumforstyrrelse, Alzheimers og Parkinsons sykdom, (2) lungekreft og luftveissykdommer, og (3) en rekke andre lidelser som følge av overflod av giftige elementer i dette materialet, inkludert arsen, kvikksølv og radioaktive elementer. De som er mest utsatt er de unge, de gamle og de med nedsatt åndedretts- og immunforsvar.Et åpent brev til medlemmer av AGU, EGU og IPCC om påstand om markedsføring av falsk vitenskap på bekostning av menneskelig og miljømessig helse (Klikk her).Jordforskere, selv de som studerer atmosfæren, er tause om den nær daglige sprøyting av luftpartikler som om den ikke eksisterer. Hvorfor ville de ikke fortelle sannheten når vitenskap handler om å fortelle sannheten, den fulle sannheten? Hva ødela jordforskere? (Klikk her)Forklaringer på tre forsøk (to vellykkede) av et desinformasjonsteam for å forårsake tilbaketrekninger av fagfellevurderte og publiserte folkehelsevitenskapelige artikler som gir bevis for langsom og lumsk aerosolforgiftning av millioner av mennesker. Ingen har rett til å forgifte mennesker, og ingen har rett til å skjule folkehelserisiko for publikum. Handlingene deres viser at de som bestiller aerosolsprøyting, kjenner godt til helserisikoen og ønsker å skjule kunnskapen for publikum. (klikk her for pdf) |

| Nettside: Offentlig bedrag av forskere i miljøforskningsbrev (klikk her)Nettside: Science Magazine Geoengineering Ikke-debatt: Uvitenhet er ikke et alternativ, men heller ikke bedrag (klikk her) Nettside: Kommunikasjon med San Diego-tjenestemenn (klikk her) PDF: Delvis liste over nettsteder som rapporterer giftig sprøyting (klikk her) Tusenvis av bilder som viser sprøyting av luftpartikler (klikk her) |

CONTRAILS FACTS

The Air Force operates many aircraft and space systems that are constantly interacting with the

environment. Atmospheric interactions such as exhaust gases forming contrails, chaff and flares

deployment that produce smoke, aerial pest or weed control spraying, or in-flight emergency

fuel releases usually have very minor environmental impacts over a very limited geographical

area. This site provides basic information and links about contrails, aircraft and space launch

exhaust emissions, chaff and flares, aerial spraying, in-flight emergency procedures, and related

topics.

Aircraft, engines, chaff, and flares can produce a variety of condensation patterns (or contrails),

exhaust plumes, vapor trails, or smoke patterns. The exhaust emissions produced by aircraft

and space launch vehicles can produce contrails that look very similar to clouds which can last

for only a few seconds or as long as several hours. Vapor trails are formed only under certain

atmospheric conditions and create a visible atmospheric wake similar to a boat propeller in

water and usually dissipate very rapidly. Chaff and flares produce unique smoke patterns that

are visibly different than a contrail but have the same color and appearance as a cloud but

which also typically dissipates very quickly. Aerial spraying for pest or weed control and fire

suppression are the only Air Force activities which involve aircraft intentionally spraying

chemical compounds (insecticides, herbicides, fire retardants, oil dispersants). In the case of an

in-flight emergency, jet fuel may be released to lighten the landing weight and minimize the risk

of fire if the aircraft should crash.

Background

The US military has played a significant historical role in the development of aircraft and space

launch vehicles, airspace management, environmental management, and public land

management procedures. In the earliest years of aviation and rocketry and up through the late

1980s, the military owned and operated the majority of the United States aircraft and space

launch fleets. Since the end of the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the USAF has been in a drawdown

and restructuring mode. In 1990, there were approximately 9,059 aircraft in the Air Force

inventory and approximately 6,126 aircraft in 2000. Of the approximately 6,228 aircraft in the

USAF fleet in 1998, 4,447 were assigned to active duty Air Force installations and 1,781 were

assigned to Guard and Reserve units, usually co-located at municipal airports. For a more

detailed discussion on the changing nature of military and civilian aviation, see A Review Of

Military Aviation And Space Issues at http://www.felsef.org/dec99.htm.

In the 1980s, commercial airline passenger

service and satellite telecommunication growth

resulted in an increase in civil aircraft and

space booster fleets with numbers almost

equivalent to the military (total of all services).

Future projections for the next 15 years

indicate that commercial aviation and space

launch fleets will become larger than the

military fleet.

The civil aviation fleet is projected to grow from

12,281 aircraft in 1997 to 25,998 in 2017. The

assumptions on growth rates and types of

aircraft are dependent on many changes in air traffic control, airspace management, and

economic growth, but the general trend for civil aviation is increasing capacity by adding more

frequent flights with smaller regional jets.

Aircraft fly along specific routes and corridors called the National Airspace System (NAS). The

NAS is comprised of the air navigation routes and infrastructure across the United States that

supports approximately 60,000 daily flights of commercial, general aviation, and military flights.

The FAA is the lead federal agency charged with the operations and maintenance of the NAS.

They manage over 5-million square miles of land routes and 23-million square miles of oceanic

routes. The FAA must balance the safety and efficiency of the NAS on a daily basis. Many

agencies and organizations are involved with the National Airspace System for a variety of

purposes: civil air carriers, general aviation, military services, and research organizations. A

typical snapshot of daily aircraft operations in the United States is shown below.

In the last ten years, there has been tremendous growth in the number of aircraft operated

around the world. The majority of aircraft seen overhead are civilian flights, particularly near

large cities. For a more detailed description of the NAS, see A Review Of Military Aviation And

Space Issues: Aerospace And Airspace (Part II) at http://www.felsef.org/jan00.htm.

Condensation Trails (“contrails”)

from Aircraft Engine Exhaust

Contrails (short for “condensation

trails”) are line-shaped clouds

sometimes produced by aircraft

engine exhaust. The combination of

high humidity and low temperatures

that often exists at aircraft cruise

altitudes allows the formation of

contrails. Contrails are composed

primarily of water (in the form of ice

crystals) and do not pose health

risks to humans. Contrails have

been a normal effect of aviation

since its earliest days. Depending

on the temperature and the amount

of moisture in the air at the aircraft

altitude, contrails can either

evaporate quickly or they can persist and grow. Engine exhaust produces only a small portion of

the water that forms ice in persistent contrails. Persistent contrails are mainly composed of

water naturally present along the aircraft flight path.

Aircraft engines emit water vapor, carbon dioxide (CO2), small amounts of nitrogen oxides

(NOx), hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, sulfur gases, and soot and metal particles formed by

the high-temperature combustion of jet fuel during flight. Of these emittants, only water vapor is

necessary for contrail formation. Sulfur gases are also of potential interest because they lead to

the formation of small particles. Particles suitable for water droplet formation are necessary for

contrail formation. Initial contrail particles, however, can either be already present in the

atmosphere or formed in the exhaust gas. All other engine emissions are considered

nonessential to contrail formation.

For a contrail to form, suitable

conditions must occur immediately

behind a jet engine in the expanding

engine exhaust plume. A contrail will

form if, as the exhaust gases cool

and mix with surrounding air, the

humidity becomes high enough (or,

equivalently, the air temperature

becomes low enough) for liquid

water to condense on particles and

form liquid droplets. If the local air is

cold enough, these newly formed

droplets then freeze and form ice

particles that make up a contrail.

Because the basic processes are

very well understood, contrail formation for a given aircraft flight can be accurately predicted if

atmospheric temperature and humidity conditions are known.

After the initial formation of ice, a

contrail evolves in one of two ways.

If the humidity is low, the contrail will

be short-lived. Newly formed ice

particles will quickly evaporate. The

resulting contrail will extend only a

short distance behind the aircraft. If

the humidity is high, the contrail will

be persistent. Newly formed ice

particles will continue to grow in size

by taking water from the surrounding

atmosphere. The resulting lineshaped contrail extends for large

distances behind an aircraft.

Persistent contrails can last for

hours while growing to several

kilometers in width and 200 to 400

meters in height. Contrails spread

because of air turbulence created by

the passage of aircraft, differences

in wind speed along the flight track,

and possibly through effects of solar

heating.

Thus, the surrounding atmosphere's

conditions determine to a large

extent whether or not a contrail will

form after an aircraft's passage, and

how it evolves. Other factors that

influence contrail formation include

engine fuel efficiency, which affects

the amount of heat and water

emitted in the exhaust plume.

Contrails become visible roughly about a wingspan distance behind the aircraft. Contrails can

be formed by propeller or jet turbine powered aircraft. During WWII, large formations of bombers

left strikingly remarkable contrail formations. Typical contrails are shown below.

The contrails formed by the exhaust at high altitude are typically white and very similar to cirrus

clouds. As the exhaust gases expand and mix with the atmosphere, the contrail diffuses and

spreads. It is very difficult to distinguish aged contrails from cirrus clouds. It is very difficult to

distinguish aged contrails from cirrus clouds. At sunsets, these contrails can be visibly eyecatching and striking as they reflect the blue, yellow, and red spectrum of the reflected sunlight.

Persistent contrails are of interest to

scientists because they affect the

cloudiness of the atmosphere.

Scientists in the United States,

Europe, and elsewhere have studied

contrail formation, occurrence, and

persistence, and research efforts on

these topics continue. Shown below

is a photo taken from the research

aircraft Falcon of the German

Aerospace Center (Deutsches

Zentrum fh r Luft- und Raumfahrt

(DLR) at about flight level 33,300

feet of an Airbus A340 with contrails

(left) and a Boeing 707 without

contrails (right). This illustrates a

scientific effort to evaluate the

effects of different engine

characteristics on contrail formation.

The Air Force uses a Boeing 707 airframe for the KC-135 refueling and E-3 AWACS aircraft.

The KC-135 fleet is in the process of upgrading to newer engines which produce fewer

emissions and noise.Scientific research on contrails was recently summarized by an

international group of experts. This summary can be found in Chapter 3 of the report, “Aviation

and the Global Atmosphere,” published in 1999 by Cambridge University Press for the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The report describes current knowledge

regarding the effects of aircraft emissions on the global atmosphere. The full report is available

from Cambridge University Press and a summary of this report is at www.ipcc.ch.

Wingtip Condensation Trails

A different type of contrail or condensation trail is caused when a wing surface or winglet causes

a cavitation of air in very humid conditions. This results in a unique vapor trail that is not formed

due to exhaust gases. The next time you fly in a commercial aircraft through a rain cloud, look

for the vapor trails that form over and around the wing. Typical fighter wingtip contrails are

shown below.

Exhaust Gases and Emissions

Often, military aircraft can be seen taking off with a black smoke appearing from the engines.

This smoke is mainly soot particles, similar to diesel engines. Commercial aircraft also produce

the same type of soot particles, but usually not to the same degree as military aircraft. This is for

two reasons: the type of fuel and the type of engines.

Most military aircraft use JP-8 jet fuel which is a blend of commercial Jet Aviation Fuel -1 (or Jet

A-1) with three extra additives. The additives are used to control ice formation, control biogrowth

(molds and slimes), and inhibit corrosion. The military uses these additives because of the

unique environments the military operates in, the type of self-sealing fuel tanks used, and the

type of metals, plastics, and sealant used on military aircraft. Several specialized aircraft like the

SR-71 and U-2 use different fuels than JP-8, but are developed from the same base stock.

Fuels research is always ongoing. The newest fuel being brought into production is JP-8+100.

Dubbed JP-8+100 because the additive package can increase the thermal stability of military

fuel by 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the improved fuel helps prevent gums and deposits that can

foul fuel lines.

Military engines are also designed with different performance characteristics than commercial

aircraft. Military aircraft and engines also tend to be older and less efficient than commercial

aircraft and produce more emissions. Engines are optimized for fuel consumption and power

rates at a particular cruising altitude. At take-off, the engines are usually very inefficient and

produce more emissions than when at the optimal cruising altitude. Older military aircraft like the

B-52 and C-130 can leave a black smoke exhaust even at cruising altitude, while aircraft like the

KC-135R with new engines produce an invisible exhaust plume. Typical pictures of aircraft

exhaust emission are shown below.

Space launch vehicles and missiles produce a different type of exhaust than aircraft. The

propulsion system on military rockets and missiles is usually made of solid rocket fuel. Missiles

and rockets produce smoke plumes as a result of the solid fuel burning. The hot gases escaping

from the motor can also create contrails, but the smoke and contrail combine to form a single

exhaust plume. For more information on Air Force propulsion and fuels programs, see the Air

Force Research Laboratory Propulsion Directorate at http://www.pr.afrl.af.mil/.

Chaff and Flares

Chaff and flares are defensive counter measures used on aircraft to confuse radar and heat

seeking missiles. Chaff is used as a decoy for radar seeking missiles and is made of glass

silicate fibers with an aluminum coating. The fibers are approximately 60% glass fiber and 40%

aluminum by weight. The typical Air Force RR-188 chaff bundle contains about 150 g of chaff or

about 5 million fibers. The fibers are 25 microns in diameter and typically 1 to 2 cm in length. In

1997, the Air Force used about 1.8 million bundles worldwide.

The amount of chaff released worldwide by all of the services is approximately 500 tons per

year. Chaff falls to the earth at a settling velocity of approximately 30 cm per second.

Atmospheric residence times range from 10 minutes for the majority of chaff released at 100 m

to approximately 10 hours for chaff released at 10,000 feet. Chaff fibers experience little

breakup before reaching the ground.

After the chaff is ejected from the aircraft and into the aircraft slipstream, the chaff packages

burst open and the fibers scatter to form a radar-reflective cloud called a chaff corridor. Each

chaff package is designed to simulate an aircraft. Several aircraft can create a chaff curtain,

consisting of thousands of false targets, which confuse the radar guidance package on a missile

so they are unable to locate the real targets within the chaff cloud.

Virtually all chaff fibers are 10-100 times larger than PM10 and PM2.5, the air particulates of

concern for public health. The primary fiber size is usually too large to be inhaled by livestock,

but if they are inhaled they do not penetrate far into the respiratory system and can be easily

cleared out. The possible nutritional effects due to chaff ingestion and the risk is minimal to nil

for both humans and livestock, considering the chemical composition of chaff (essentially

identical to soil) and low chaff loading on the environment. Chaff decomposing in water has no

adverse impacts on water chemistry or aquatic life.

Flares are of two types: decoy flares that protect aircraft from infrared missiles, and ground

illumination flares. Decoy flares are typically made of magnesium that burns white-hot and are

designed to defeat a missile's infrared (IR) tracking capability. The intense heat of the

pyrotechnic candle consumes the flare housing. Common aerial flares are: ALA-17/B, M-206,

MJU-2, MJU-7 A/B, MJU-10/B, MJU-23/B, and RR-119.

Ground illumination flares, are designed to descend by parachute and provide up to 30 minutes

of illumination of ground targets or activities. Typical flares are the LUU-1, LLU-5, and LLU-2B.

A typical LLU-2B sectional is shown below.

The ground illumination flare enhances a pilot's ability to see targets while using Night Vision

Goggles (NVGs). Flares burn at uneven rates and fluctuate in brightness and are not used as

frequently as in the past as the intense light interferes with the newer NVGs more sensitive

sensors.

The composition and materials of flares used by the military are similar to standard flares used

for aerial, highway and marine purposes. (Skyline). While unburned decoy flares falling from

high altitude could be dangerous, flares are designed to burn up during the descent (even the

aluminum casing is burned).

Chaff and flares are deployed on most Air Force aircraft from a common MJU-11 Chaff/Flare

magazine that is integrated with the warning receiver (a device that alerts the aircraft a missile

has locked onto the aircraft). The magazine has a capacity of 30 RR-188 or 30 M-206 flares.

A very thorough independent description of military systems, equipment, and capabilities is

published by the American Federation of Scientists.

Typical chaff and flare deployments and patterns are shown in the following pictures.

Aerial Spraying

There are some specific uses of commercial, private, and military aviation where chemicals are

introduced in the atmosphere. The most common association of aerial chemical release is

spraying for insects, either as crop dusting or mosquito prevention measures. These activities

are typically performed at low altitude levels and produce a mist spray that drops to the earth's

surface.

The only unit in the Air Force capable of aerial

spray operations to control disease-carrying pests

and insects is the AFRC's 910th Airlift Wing,

Youngstown-Warren Air Reserve Station, Ohio

(http://www.afrc.af.mil/units/910aw/default.htm).

The aerial spray mission uses four specially

configured C-130 Hercules shown below. Aerial

spraying enables large parcels of land or water to

be treated safely, quickly, accurately, and cheaply.

This is the only fixed wing aerial-spray capability in

the Department of Defense.

The mission started back in World War II, when legions of American GIs fell victim to malaria

and dengue fever, diseases spread by mosquitoes. The mission was taken over from the active

force in 1973. Although most of the unit's missions are initiated by the Department of Defense,

its services are also requested by local, state and other federal agencies and coordinated the

Center for Disease Control. The most common missions flown are for mosquito, sand flea and

weed control. Several states have also requested support to combat grasshoppers and locusts.

Aerial spray missions have been flown in Puerto Rico, Panama, Guam and the Azores.

The chemical compounds used for mosquito control are EPA controlled and the Air Force uses

two primary brands; Dibrom and Anvil 10+10. Dibrom is manufactured by AMVAC Chemical

Corporation and is classified as a Naled compound. Naled is an organophosphate insecticide

that has been in use since 1959. It is used primarily for controlling adult mosquitoes but is also

used on food and food crops, greenhouses and pet flea collars. Naled is applied using UltraLow Volume sprayers which dispense very fine aerosol droplets which kills the adult mosquito

on contact. Naled is applies at a maximum aerial spray rate of 0.8 ounces of active ingredient

per acre. Anvil 10+10 is manufactured by Clarke Mosquito Control Products, Inc and is a

Sumithren, also known as a Synergized Synthetic Pyrethoid. Anvil 10+10 is applied using UltraLow Volume sprayers at a maximum aerial spray rate of 0.62 ounces of active ingredient per

acre.

The chemical compounds used for herbicide weed control are EPA controlled and the Air Force

uses Dupont Krovar I DF and Dow Agro Sciences Tordon K. Krovar I DF comes in granular

form, is mixed with water and applied as an aerosol to control annual weeds at a rate of 4-6

pounds mixed with 40-100 gallons of water per acre. Tordon K is used as a herbicide to control

broadleaf weeds, woody plants, and vines on non-crop areas such as forest planting sites,

industrial manufacturing sites, rights-of-way such as electrical power lines, communications

lines, pipelines, roadsides, railroads, and wildlife openings. Tordon K is applied at a maximum of

2 quarts per acre.

The 910th Airlift Wing has formed an Oil Dispersant Working Group, and is working with

industry and government agencies to test aerial spray methods of controlling major offshore oil

spills in coastal waters of the United States. The unit has six Modular Aerial Spray Systems

(MASS) and four aircraft modified to accept the MAAS. Each MASS has a 2,000 gallon capacity

and flow rate are set at 232 gallons per minute. The aircraft flies at 200 Knots Ground Speed at

about 100 feet which covers a swath width of 100 feet for an average application rate of flow

rate of 5 gallons per acre (variable 3-15 gallons per acre). Total spray-on time for 2,000 gallons

lasts about 8 minutes and 30 seconds.

Photographs which show military aircraft with sprays coming from unusual locations on the

aircraft are usually re-touched photos (a process that is easy to create using common computer

programs).

Cloud Seeding and Fire Suppression

For a number of years commercial companies

have been involved in cloud seeding and fire

suppression measures. Cloud seeding

requires the release of chemicals in the

atmosphere in an effort to have water crystals

attach themselves and become heavy enough to produce rain. The Air Force does not have a

cloud seeding capability.

Fire suppression involves dumping chemicals onto a

fire using cargo-type aircraft or helicopters. The 731st

Airlift Squadron assigned to the 302nd Airlift Wing,

Peterson Air Force Base, CO., is trained in the use of

modular airborne fire fighting systems that help

firefighting efforts of the U.S. Forest Service by

dropping retardant chemicals directly onto fires. The

unit's C-130s are loaded with a system designed to

airdrop fire-retardant chemicals used in fighting forest

fires and fertilizing the forest to generate quick

regrowth. The 302nd AW has conducted firefighting response in Colorado, California, Oregon

and Idaho.

U.S. forest fires generally occur in desolate, almost

inaccessible geographical areas. The U.S. Forest

Service turned to air power to help its ground fire

fighting units quickly contain and suppress these fires.

Over the years, the forest service has developed a

highly effective air-attack organization and air tanker

fleet to deal with the forest fire emergency.

In 1970, however, numerous catastrophic forest fires

erupted in southern California, severely overloading the

air tanker fleet's ability to cope with them all. This led to several U.S. Congressmen requesting

the U.S. Air Force help the forest service by making military aircraft available as a back-up

measure. This in turn led to the development of the Modular Airborne Fire Fighting System

(MAFFS). The system is designed to quickly adapt military C-130 aircraft from a military role to

a fire-suppression role.

Since 1974, the U.S. Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard units

strategically located near high-incident forest fire areas have been

equipped with these MAFFS units, and have sent selected aircrews to

the aircrew training school for instruction in forest service air operations

and procedures.

The MAFFS System is a modular, reusable airborne system for

deploying water and fire retardant chemicals from aircraft in flight. It

consists of seven airborne modules and one ground air compressor module. The system can be

loaded on a C-130 aircraft in two hours, and filled with retardant and compressed air in 15 to 20

minutes. The system is self-contained and requires no aircraft modifications. Each system

weighs 10,500 pounds empty, and has a capacity of 2,700 gallons.

The entire load of retardant is discharged over a fire in 6 to 8 seconds.

Other AFRC aircraft shuttle Forest Service personnel and equipment to fire areas when the

emergency requires a swift deployment to the fire line. This increased mobility allows more

efficient use of Forest Service resources.

In-flight Emergency Fuel Release

Another common, but infrequent, procedure is the release, or venting, of fuel as a safety

measure. If an in-flight emergency (IFE) is declared, a pilot will want to land the aircraft with as

light a load as possible to prevent the possibility of damaging the aircraft and/or causing a fuel

leak on landing. In order to lighten the fuel load a pilot can continue to fly until the fuel is burned

or vent the fuel into the atmosphere. Fuel that is released, or vented, typically atomizes into a

fine spray as it is released and typically evaporates before it reaches the ground. JP-8 jet fuel

released at low altitudes appears as a fine mist and may not volatilize before reaching the

ground surface. The release of fuel does not produce a contrail and appears more like a smoke

pattern that dissipates quickly.

The “Chemtrail” Hoax

A hoax that has been around since 1996 accuses the Air Force of being involved in spraying the

US population with mysterious substances and show various Air Force aircraft “releasing

sprays” or generating unusual contrail patterns. Several authors cite an Air University research

paper titled “Weather as a Force Multiplier: Owning the Weather in 2025”

(http://www.au.af.mil/au/database/research/ay1996/acsc/96-025ag.htm) that suggests the Air

Force is conducting weather modification experiments. The purpose of that paper was part of a

thesis to outline a strategy for the use of a future weather modification system to achieve

military objectives and it does not reflect current military policy, practice, or capability.

The Air Force's policy is to observe and forecast the weather. The Air Force is focused on

observing and forecasting the weather so the information can be used to support military

operations. The Air Force is not conducting any weather modification experiments or programs

and has no plans to do so in the future.

The “Chemtrail” hoax has been investigated and refuted by many established and accredited

universities, scientific organizations, and major media publications.

Claims and Facts

Claim: Long-lasting contrails are something new and they have abnormal characteristics.

Fact: Contrails can remain visible for very long periods of time with the lifetime a function of the

temperature, humidity, winds, and aircraft exhaust characteristics. Contrails can form many

shapes as they are dispersed by horizontal and vertical wind shear. Sunlight refracted or

reflected from contrails can produce vibrant and eye-catching colors and patterns. Observation

and scientific analysis of contrails and their duration date back to at least 1953.

Claim: Grid patterns of contrails in the sky are evidence of a systematic spraying operation.

Fact: The National Airspace System of the United States is orientated in an east-west and

north-south grid with aircraft flying at designated 2000 foot increments of elevation. Contrails

formed by aircraft may appear to form a grid as the winds disperse the contrails. More contrails

are seen in recent years due to the growth in the civil aviation market. The FAA is responsible

for the NAS and Air Force aircraft operate under the same rules and procedures as civilian

aircraft when using the NAS.

Claim: There are reported outbreaks of illness after the appearance of “Chemtrails”

Fact: There is no such thing as a “Chemtrail”. Contrails are safe and are a natural

phenomenon. They pose no health hazard of any kind. If there are massive outbreaks of

illnesses, your local health department should be able to tell you if it is an abnormal event. Local

health departments generally network together when they start seeing problems. If there is a

problem, the CDC will get involved.

Claim: Samples taken have shown the presence of the “DOD patented” bacteria pseudomonas

fluorescens.

Fact: The bacteria claimed to be DOD developed and patented is actually a common, naturally

occurring bacteria. The U.S. Patent Office (www.uspto.gov) lists 181 patents involving

pseudomonas fluorescens, none of which are held by DOD.

Links to Related Sites

• FAA Office of Aviation Research – http://research.faa.gov/aar/

• FAA Office of Environment and Energy – http://aee.hq.faa.gov/

• DOT Bureau of Transportation Statistics – http://www.bts.gov/

• Center For Disease Control and Prevention – http://www.cdc.gov/

• EPA Office of Pesticide Programs – http://www.epa.gov/pesticides

• International Civil Aviation Organization – http://www.icao.int/

• Air Transport Association – http://www.air-transport.org/

• Aerospace Industries Association – http://www.aia-aerospace.org/

• Federation of American Scientists – http://www.fas.org/index.html

• General Electric Aircraft Engines – http://www.geae.net/

• Pratt and Whitney Aircraft Engines – http://www.pratt-whitney.com/engines/

• Rolls-Royce Aircraft Engines – http://194.128.225.11/defence/milp001.htm

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1999. Aviation and the Global

Atmosphere. A Special Report of IPCC Working Groups I and III in collaboration with the

Scientific Assessment Panel to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone

Layer. Published for the IPCC by Cambridge University Press. J.E. Penner, D.H. Lister, D.J.

Griggs, D.J. Dokken, and M. McFarland, editors. 373 pp.

Appleman, H., 1953. The formation of exhaust condensation trails by jet aircraft. Bulletin of the

American Meteorological Society 34: 14-20. Brewer, A.W., 1946. Condensation trails. Weather

1: 34-40.

Chipley, Michael Ph.D. A Review Of Military Aviation And Space Issues, The Forum For

Environmental Law, Science, Engineering And Finance, December 1999.

Chipley, Michael Ph.D. A Review Of Military Aviation And Space Issues: Aerospace And

Airspace” (Part II), The Forum For Environmental Law, Science, Engineering And Finance,

January 2000.

Spargo, B.J., Environmental Effects of RF Chaff, Naval Research Laboratory, Washington,

D.C., August 31, 1999.

Pike, John, Aircraft Weapon Loads, Federation of American Scientists, 2000.

Aircraft and Contrails. EPA publication number EPA430-F-00-005. 6 pp EPA, 2000.

(www.epa.gov/otaq/aviation.htm)

Layman's Library

Contrails – Contrails, or condensation trails, are “streaks of condensed water vapor created in

the air by an airplane or rocket at high altitudes.”(Webster's Dictionary). Contrails are the result

of normal emissions of water vapor from jet engines. At high altitudes, water vapor condenses

and turns into a visible cloud. Contrails form when hot humid air from jet engines mixes with the

surrounding air in the atmosphere which is drier and colder. The mixing is a result of turbulence

generated by the jet engine exhaust. The water vapor in the jet exhaust then condenses and

forms a cloud. The rate at which contrails dissipate is entirely dependent upon weather

conditions and altitude. If the atmosphere is near saturation, the contrail may exist for some

time. Conversely, if the atmosphere is dry, the contrail will dissipate quickly.

Contrail Grid Patterns – Numerous contrails are usually over “air routes”, or highways in the

sky. Aircraft fly in all different directions at any time, and numerous contrails may seem to

“crisscross”. Although contrails may appear to cross, the trails can actually be from planes

separated by significant altitude and time.

Chaff – Chaff are small bundles of aluminum coated fibers that create a large radar reflection. A

radar seeking missile is unable to distinguish an aircraft from the chaff and loses the lock on the

aircraft.

Chemtrails – Chemtrails is a term coined to suggest contrails are formed by something other

than a natural process of engine exhaust hitting the cold air in the atmosphere.

Ethylene dibromide – Ethylene dibromide, or EDB, is a pesticide that was used commercially

before being banned by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1983. During WW II, EDB was

used as an additive in aviation gasoline to help stop lead in the aviation gasoline from plating

out on valves. Jet fuels, including JP-8 have never contained EDB. Soil samples showing the

presence of EDB are most likely residuals from previous use as a pesticide. Webster's

dictionary definition of EDB: “: a colorless toxic liquid compound C2H4Br2 that is used chiefly as

a fuel additive in leaded gasolines, that has been found to be strongly carcinogenic in laboratory

animals, and that was used formerly in the U.S. as an agricultural pesticide — abbreviation

EDB.”

JP-8 Jet Fuel – JP-8 jet fuel consists of kerosene, a petroleum distillate fraction purchased to

specification. The specification requires that the fuel producer meet a range of chemical and

physical properties to ensure proper aircraft operation. Fuel additives are allowed, but are highly

controlled. Additives include antioxidants, metal deactivators, corrosion inhibitors, fuel system

icing inhibitor, and a static dissipater additive.

Rocket Exhaust – The exhaust plume generated by solid or liquid fueled rockets. Solid rocket

motors are usually made of ammonium perchlorate and typically create light colored exhaust

emissions. The exhaust is mainly carbon dioxide and water, but may also have high levels of

hydrochloric acid formed, but which disperses rapidly. Liquid fuel rockets are generally kerosene

and Liquid Oxygen (LOX) and produce an exhaust, which is darker and similar to aircraft

exhaust. The exhaust is primarily carbon dioxide and water, but may contain nitrous oxides,

sulfides, and soot particles.

Stratospheric Ozone – The ozone formed in the upper atmosphere through the interaction of

the sun's energy and oxygen and which provides the natural shielding effect for the earth from

UV rays. This ozone layer is susceptible to destruction by chlorinated compounds and is

generally associated with the ozone hole over the Antarctic. Ozone in the lower atmosphere and

ground level is generally a by-product of motor vehicle fuel combustion that forms NOx as a

precursor which then forms ozone. This ozone is often seen as smog in most major cities.

Vapor Trails – The trail formed behind an aircraft as result of air flowing over a surface which

creates a cavity in the air, similar to a boat propeller in water.

+ There are no comments

Add yours